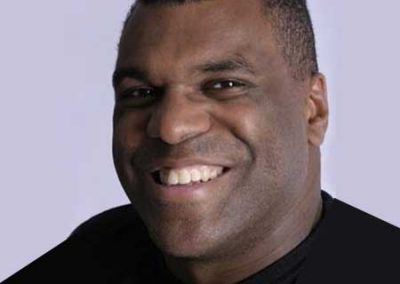

Get to Know Me

Joshua Michael Stewart is a poet and musician who has had poems published in the Massachusetts Review, Salamander, Plainsongs, Brilliant Corners, and many others. His books are, Break Every String, (Hedgerow Books, 2016) and, The Bastard Children of Dharma Bums, (Human Error Publishing, 2020). His albums, Three Meditations, and Ghost in the Room, can be found on Apple Music, Spotify, Amazon, and many other platforms. Visit his web site at www.joshuamichaelstewart.com, or better yet, interact with him at www.facebook.com/joshua.m.stewart.526/.

For this column Joshua will explore poetry, music, and Buddhism, and how they all intersect with each other. He will delve into assorted poetic forms and he will specifically highlight contemporary poets from the New England area, and the poets associated with classical Japanese and Chinese poetry.

Hello there!

I thought by way of introduction, I’d share a handful of my own poems that span a wide range of themes and forms. Naturally, as most poets, I let the work speak for itself.

Quills

Today a man pressed a pillow

over his 7-month-old son’s face,

then strangled the baby’s mother

(who was also his 16-year-old daughter),

called his mother, confessed,

then drove out into the woods and shot

himself in the cab of his pickup.

A porcupine waddles through a field

not far from my house. I’ve never fired

a round at anything not glass or tin,

but the summer after my mother loaded

me on a plane to go live with my father

was spent nailing earthworms to 2x4s

leaned along the backyard fence.

Hammer thwacks echoed off the shed

as morning haze ghosted

through surrounding pines. The worms

writhed as I pierced their skin,

blood and shit smeared the boards,

the crucified bodies dried and curled

under the sun my parents both shared.

The pain we receive, the little it takes

to give it tenfold. I won’t measure evil

out of units of illness and despair,

but while the porcupine munches

on clover, I’ll rest on a stone wall,

allow the sun to burn my neck red,

my hands finally at peace in my lap.

Originally published in The Massachusetts Review

November Praise

The smell of ferns and understory

after rain. The tick, tick, of stove,

flame under kettle. Bing Crosby,

and not just the Christmas records.

Cooking meat slowly off the bone,

and every kind of soup and stew.

To come this close to nostalgia,

but go no further, leaving behind

the boy who wore loneliness

like boots too big for his feet.

That time of evening,

when everything turns blue

in moonlight, when darkness

has yet to consume all for itself.

Originally published in Nine Mile Magazine

Okay, okay, okay. I know I said I’d let the poems speak for themselves, but for this next poem I need to state the following: The first section of my most recent book, The Bastard Children of Dharma Bums, consists of a series of poems that are sculpted poems, essentially erasure poems without the erased lines, taken from each chapter of Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums. I manipulate the lines, punctuation, and in some cases, the tense of a word, changing “broke” to “break,” for an example, but otherwise the words within each poem are as they fall within Kerouac’s novel. Here is one of those poems:

The Bastard Children of Dharma Bums #34

Raspberry Jell-O in the setting sun

poured through unimaginable craigs.

Rose-tint hope—brilliant and bleak.

Ice fields and snow raging mad.

I read snowy air and woodsmoke.

The wind dark, clouds forge.

The sing in my stovepipe absorbs

vaster, darker storm closing in

like a surl of silence. No starvation

turmoiling. My shadow the rainbow

I haloed. Your life a raindrop.

I stood in rose dusk, meditated

in half-moon thunder.

My mother’s love drenching rains

washed and washed.

I called Han Shan in the mountains.

I called Han Shan in morning fog.

I closed my eyes, yelled dark wild

down in my garbage pit.

My hair long in the mirror.

My skin soaking pristine light.

My fire roaring. I hear the radio

singing, She was the wind

which passes through everything.

Birds rejoicing sweet blueberries

for the last time. Sitting, I twisted

real life and cried cascades

answering the meditation bell.

I know desolation.

I owe gritty love back to this world.

These last two poems that I leave you with are from my first collection of poems, Break Every String. I hope you’ve enjoyed these poems and look forward to reading future essays, reviews, and interviews with other contemporary poets.

Snow Angels

Each night they stare into the sky

and wonder why even with wings

they can never get off the ground.

Good reason for their creator

to take three steps, cock his head

and disown his gift to the world.

Abandonment: a likely origin of anyone’s

lack of faith. And faith: precisely what’s needed

to soar in the purple abyss of winter.

We step out into our lives like sun slicing

between buildings and perform this one angelic

act that melts from our consciousness.

We return to our houses to accomplish

something important, leaving behind

the ones who don’t know any better,

who see the wings as open arms,

snow as flesh, and are willing to lie back down.

Born in the USA

We were pumping our fists with Springsteen,

chanting the chorus as Reagan galloped

the campaign trail, still pretending

to be a cowboy, and the old man who lived

in the blue house with the white fence

lined with rosebushes was handing out mints

from a bowl made out of a buffalo skull.

Uncle Bob chopped off his thumbs

in a metal press on his first day on the job.

My father returned to Khe Sahn sleepwalking

past our bedrooms, shouting out the names

of smoke and moon. He had a woman he loved

in Saigon, sang The Boss. Across the bay—

Ferris wheel lights and roller coaster screams.

Child Services found my grandmother unfit

to adopt. An ambulance in front of the blue house

with the white fence lined with rosebushes.

A white sheet. The bones and feathers

of a dead seagull—a ship wreck

on a rocky shore lapped by green waves.

On their lunch break, my father, my uncles,

and both my grandfathers, their names

embroidered on their grease-stained shirts,

stepped out of the factory and coughed up

their paychecks to their wives idling in Regals,

Novas, and Gremlins. Out by the gas fires

of the refinery. My father’s handlebar mustache

terrified me. My brother built me castles

out of blankets and chairs, larger than the house

that confined them. Taught me how to leap

off the couch like Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka,

how to moonwalk and breakdance. He’d go on

to teach me that disappointment’s a carcinogen.

My father took cover behind the Lay-Z-boy

in his underwear. My grandmother offered

a pregnant runaway a place to stay in exchange

for her baby. When the plant relocated to Mexico,

my father brought home a pink slip heavier

than a Huey Hog. The rosebushes became thorny

switches. Over ham steaks and mashed potatoes,

our parents poured out their divorce.

We had to decide who we wanted to live

with before leaving the table. I’d go

wherever my brother went: that meant Mom.

My father took a job out of state.

My mother took a boyfriend, who

dragged his unemployment into a bar

called The Pit, then staggered

into our house knocking over houseplants,

and I was the one ordered to clean

the carpets with the wet/dry vac. We’d sneak

out of the house at 3AM to swim

in the neighbor’s pool, or ping rocks

off hurtling freight trains. The city condemned

the blue house with the paint-chipped fence.

My mother’s eye, blackened. We slept in parks,

better than home. She stood at the sink,

sobbed, scrubbed blood-splotches

out of her white jacket with a soapy sponge.

Wouldn’t press charges. My brother bought

a dime bag and a revolver from a guy named Kool-Aid.

My mother was crowned a welfare queen, and drove

a Cadillac assembled out of political mythology.

I smoked my first joint on the roof of a movie theater

with my brother and the stars. An after-school ritual:

stepping over the passed-out boyfriend to grab

a Coke out of the fridge. We spray-painted

gang insignias across the boarded-up windows

of the blue house with splintered teeth. The boyfriend

could whip up one hell of an omelet. We didn’t hate

him on Sunday mornings. My mother’s stiches.

We swiped a bottle of Mad Dog, drank it while eating

peanut butter & jelly sandwiches. My mother stashed

bottles of gin in the leather boots my father bought

for their last Christmas together. Twice they called

me into the principal’s office because a knife fell out

of my pocket at recess. We turned abandoned factories

into playgrounds, busted out the windows with tornadic rage.

Somebody was asking for it, and somebody was going to get it.

I overheard a teacher tell my mother, “He’s going to grow up

to kill somebody.” Thanks to the Black Panthers,

this white boy had free breakfast at school.

My brother waited until the boyfriend was drunk

on the toilet to burst in swinging a baseball bat.

Later that night while taking a bath, I fished

out a tooth biting me in the ass. Backhoes

and bulldozers devoured the blue house

with the collapsing roof. We rewound

and played back the catastrophic loss

that plumed over Cape Canaveral

on our VCRs. The boyfriend slammed

a stolen van into a tree. She’d pour me

a bowl of Cheerios, pour herself a Scotch.

The boyfriend’s dentist kept good records.

“I’m sending you to your father.”

Son don’t you understand now? Front-page news:

firefighters dousing the mangled inferno.

Got in a little hometown jam.

I stood before a judge, pled guilty to

shoplifting Christmas lights, the kind that twinkle.

Also from M the Media Project

Trenda Loftin

Chap Hop! &has Electro-swing

From Newport Jazz Festival

News Features

From Newport Jazz Festival

On Being a White Jerk

Playing, Praying & Tailgating

Wanting More than Rural Charm

Video Channels

Mental Suppository Podcast

On the Rocks Politica

SMG’s ‘Are We Here Yet’?

Hello there!

I thought by way of introduction, I’d share a handful of my own poems that span a wide range of themes and forms. Naturally, as most poets, I let the work speak for itself.

Quills

Today a man pressed a pillow

over his 7-month-old son’s face,

then strangled the baby’s mother

(who was also his 16-year-old daughter),

called his mother, confessed,

then drove out into the woods and shot

himself in the cab of his pickup.

A porcupine waddles through a field

not far from my house. I’ve never fired

a round at anything not glass or tin,

but the summer after my mother loaded

me on a plane to go live with my father

was spent nailing earthworms to 2x4s

leaned along the backyard fence.

Hammer thwacks echoed off the shed

as morning haze ghosted

through surrounding pines. The worms

writhed as I pierced their skin,

blood and shit smeared the boards,

the crucified bodies dried and curled

under the sun my parents both shared.

The pain we receive, the little it takes

to give it tenfold. I won’t measure evil

out of units of illness and despair,

but while the porcupine munches

on clover, I’ll rest on a stone wall,

allow the sun to burn my neck red,

my hands finally at peace in my lap.

Originally published in The Massachusetts Review

November Praise

The smell of ferns and understory

after rain. The tick, tick, of stove,

flame under kettle. Bing Crosby,

and not just the Christmas records.

Cooking meat slowly off the bone,

and every kind of soup and stew.

To come this close to nostalgia,

but go no further, leaving behind

the boy who wore loneliness

like boots too big for his feet.

That time of evening,

when everything turns blue

in moonlight, when darkness

has yet to consume all for itself.

Originally published in Nine Mile Magazine

Okay, okay, okay. I know I said I’d let the poems speak for themselves, but for this next poem I need to state the following: The first section of my most recent book, The Bastard Children of Dharma Bums, consists of a series of poems that are sculpted poems, essentially erasure poems without the erased lines, taken from each chapter of Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums. I manipulate the lines, punctuation, and in some cases, the tense of a word, changing “broke” to “break,” for an example, but otherwise the words within each poem are as they fall within Kerouac’s novel. Here is one of those poems:

The Bastard Children of Dharma Bums #34

Raspberry Jell-O in the setting sun

poured through unimaginable craigs.

Rose-tint hope—brilliant and bleak.

Ice fields and snow raging mad.

I read snowy air and woodsmoke.

The wind dark, clouds forge.

The sing in my stovepipe absorbs

vaster, darker storm closing in

like a surl of silence. No starvation

turmoiling. My shadow the rainbow

I haloed. Your life a raindrop.

I stood in rose dusk, meditated

in half-moon thunder.

My mother’s love drenching rains

washed and washed.

I called Han Shan in the mountains.

I called Han Shan in morning fog.

I closed my eyes, yelled dark wild

down in my garbage pit.

My hair long in the mirror.

My skin soaking pristine light.

My fire roaring. I hear the radio

singing, She was the wind

which passes through everything.

Birds rejoicing sweet blueberries

for the last time. Sitting, I twisted

real life and cried cascades

answering the meditation bell.

I know desolation.

I owe gritty love back to this world.

These last two poems that I leave you with are from my first collection of poems, Break Every String. I hope you’ve enjoyed these poems and look forward to reading future essays, reviews, and interviews with other contemporary poets.

Snow Angels

Each night they stare into the sky

and wonder why even with wings

they can never get off the ground.

Good reason for their creator

to take three steps, cock his head

and disown his gift to the world.

Abandonment: a likely origin of anyone’s

lack of faith. And faith: precisely what’s needed

to soar in the purple abyss of winter.

We step out into our lives like sun slicing

between buildings and perform this one angelic

act that melts from our consciousness.

We return to our houses to accomplish

something important, leaving behind

the ones who don’t know any better,

who see the wings as open arms,

snow as flesh, and are willing to lie back down.

Born in the USA

We were pumping our fists with Springsteen,

chanting the chorus as Reagan galloped

the campaign trail, still pretending

to be a cowboy, and the old man who lived

in the blue house with the white fence

lined with rosebushes was handing out mints

from a bowl made out of a buffalo skull.

Uncle Bob chopped off his thumbs

in a metal press on his first day on the job.

My father returned to Khe Sahn sleepwalking

past our bedrooms, shouting out the names

of smoke and moon. He had a woman he loved

in Saigon, sang The Boss. Across the bay—

Ferris wheel lights and roller coaster screams.

Child Services found my grandmother unfit

to adopt. An ambulance in front of the blue house

with the white fence lined with rosebushes.

A white sheet. The bones and feathers

of a dead seagull—a ship wreck

on a rocky shore lapped by green waves.

On their lunch break, my father, my uncles,

and both my grandfathers, their names

embroidered on their grease-stained shirts,

stepped out of the factory and coughed up

their paychecks to their wives idling in Regals,

Novas, and Gremlins. Out by the gas fires

of the refinery. My father’s handlebar mustache

terrified me. My brother built me castles

out of blankets and chairs, larger than the house

that confined them. Taught me how to leap

off the couch like Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka,

how to moonwalk and breakdance. He’d go on

to teach me that disappointment’s a carcinogen.

My father took cover behind the Lay-Z-boy

in his underwear. My grandmother offered

a pregnant runaway a place to stay in exchange

for her baby. When the plant relocated to Mexico,

my father brought home a pink slip heavier

than a Huey Hog. The rosebushes became thorny

switches. Over ham steaks and mashed potatoes,

our parents poured out their divorce.

We had to decide who we wanted to live

with before leaving the table. I’d go

wherever my brother went: that meant Mom.

My father took a job out of state.

My mother took a boyfriend, who

dragged his unemployment into a bar

called The Pit, then staggered

into our house knocking over houseplants,

and I was the one ordered to clean

the carpets with the wet/dry vac. We’d sneak

out of the house at 3AM to swim

in the neighbor’s pool, or ping rocks

off hurtling freight trains. The city condemned

the blue house with the paint-chipped fence.

My mother’s eye, blackened. We slept in parks,

better than home. She stood at the sink,

sobbed, scrubbed blood-splotches

out of her white jacket with a soapy sponge.

Wouldn’t press charges. My brother bought

a dime bag and a revolver from a guy named Kool-Aid.

My mother was crowned a welfare queen, and drove

a Cadillac assembled out of political mythology.

I smoked my first joint on the roof of a movie theater

with my brother and the stars. An after-school ritual:

stepping over the passed-out boyfriend to grab

a Coke out of the fridge. We spray-painted

gang insignias across the boarded-up windows

of the blue house with splintered teeth. The boyfriend

could whip up one hell of an omelet. We didn’t hate

him on Sunday mornings. My mother’s stiches.

We swiped a bottle of Mad Dog, drank it while eating

peanut butter & jelly sandwiches. My mother stashed

bottles of gin in the leather boots my father bought

for their last Christmas together. Twice they called

me into the principal’s office because a knife fell out

of my pocket at recess. We turned abandoned factories

into playgrounds, busted out the windows with tornadic rage.

Somebody was asking for it, and somebody was going to get it.

I overheard a teacher tell my mother, “He’s going to grow up

to kill somebody.” Thanks to the Black Panthers,

this white boy had free breakfast at school.

My brother waited until the boyfriend was drunk

on the toilet to burst in swinging a baseball bat.

Later that night while taking a bath, I fished

out a tooth biting me in the ass. Backhoes

and bulldozers devoured the blue house

with the collapsing roof. We rewound

and played back the catastrophic loss

that plumed over Cape Canaveral

on our VCRs. The boyfriend slammed

a stolen van into a tree. She’d pour me

a bowl of Cheerios, pour herself a Scotch.

The boyfriend’s dentist kept good records.

“I’m sending you to your father.”

Son don’t you understand now? Front-page news:

firefighters dousing the mangled inferno.

Got in a little hometown jam.

I stood before a judge, pled guilty to

shoplifting Christmas lights, the kind that twinkle.

Also from M the Media Project

Trenda Loftin

Chap Hop! &has Electro-swing

From Newport Jazz Festival

News Features

From Newport Jazz Festival

On Being a White Jerk

Playing, Praying & Tailgating

Wanting More than Rural Charm

Video Channels

Mental Suppository Podcast

On the Rocks Politica

SMG’s ‘Are We Here Yet’?

Interested in advertising with us? Perhaps you want a unique way to support the economic development work we accomplish while getting access to our intelligent and informed listeners? Join our roster of supporters. Click that button below to find out more.